The first notice of Dimitri Tiomkin’s interest in making a film version of the Isabel Colegate novel, Statues in a Garden, dates from the fall of 1965. The novel, published in Great Britain the previous year, had made its way across the Atlantic to New York and publisher Alfred A. Knopf was preparing an American edition. In September of 1965, Knopf editor Patrick Gregory personally loaned the British first edition to Tiomkin when both were in New York. Now, in a letter to Tiomkin a fellow editor at Knopf, Thomas C. F. Lowry, appeals to Tiomkin to return “our only copy.” The handwritten postscript reads, “We’re really in a bind on this good novel (which I hope you liked) and trust you will return soonest.” By the time Lowry’s letter reaches Tiomkin’s home in Los Angeles, the composer-turned-producer had left for Europe so his secretary, Joan Schoenfeld, returned the book to Knopf via the mail.

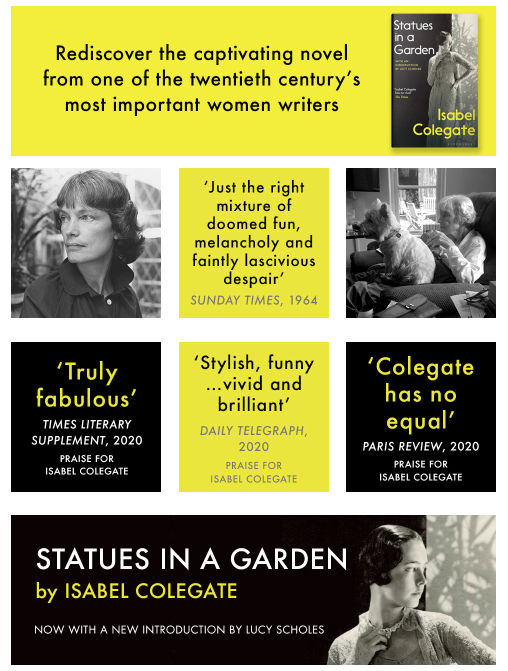

Prior to Statues in a Garden, English writer Isabel Diana Colegate (1931- ) had written three novels after pivoting from an early career as a literary agent while still in her twenties. Of Colegate, fellow writer Elizabeth Evershed wrote in 2011: “Statues in a Garden (1964), the most accomplished of her early books, is a clear forerunner to her most successful novel, The Shooting Party (1981), in its portrait of the waning powers of the aristocracy in the twentieth century, and the shadow and disruption to their existence and way of life that is brought about by the First World War.”

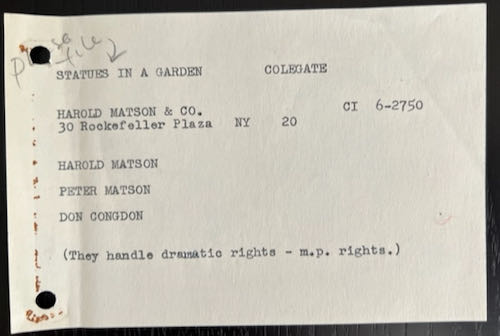

A cryptic note in Tiomkin’s Statues in a Garden file from early 1966 names literary agent Harold Matson in connection with pursuing motion picture rights.

Meanwhile, the American edition of the novel is issued by Knopf in March 1966.

An entire year passes. (1966 would become the first year that would not see the release of a Tiomkin-scored film after a three-decade run beginning in 1935.) Tiomkin sends a copy of the American edition of Statues to his publicist friend Max Bercutt at Warner Bros. in March 1967. (Bercutt was involved in other Tiomkin-led projects around this time, including AZEF, HOME IS THE SAILOR, and TCHAIKOVSKY.)

Max Bercutt and Dimitri Tiomkin shake hands, circa mid-1960s

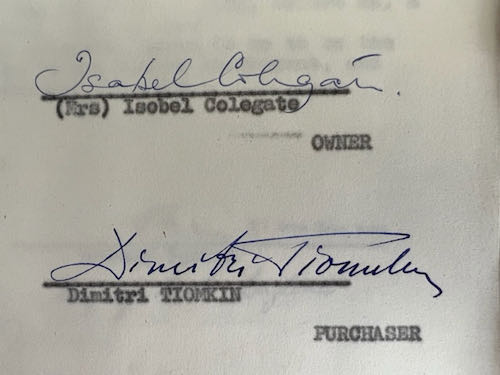

In June 1967, Tiomkin options the dramatic rights from Colegate for a film version of her novel. The option is for 18 months, with a six-month extension.

The signatures of Isabel Colegate and Dimitri Tiomkin from the 1967 option agreement.

Statues is not the only story property that Tiomkin is vying to produce. James Ramsey Ullman’s The Day on Fire, Graham Greene’s May We Borrow Your Husband, and Robin Bean’s Ring Once for Angels are all on deck; however, by January 1968, Tiomkin is actively pursuing the production of Statues in a Garden while in London.

Tiomkin is in contact with Gerry Blattner. Blattner cut his teeth overseeing Warner Bros. productions filmed at Elstree Studios and elsewhere in Europe and went on to head Warner Bros. European Film Productions. Blattner served as production manager for LAND OF THE PHARAOHS (1955) and produced THE SUNDOWNERS (1960), both films scored by Tiomkin.

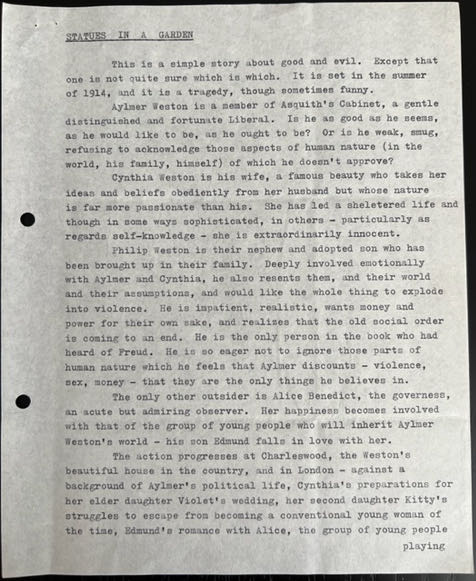

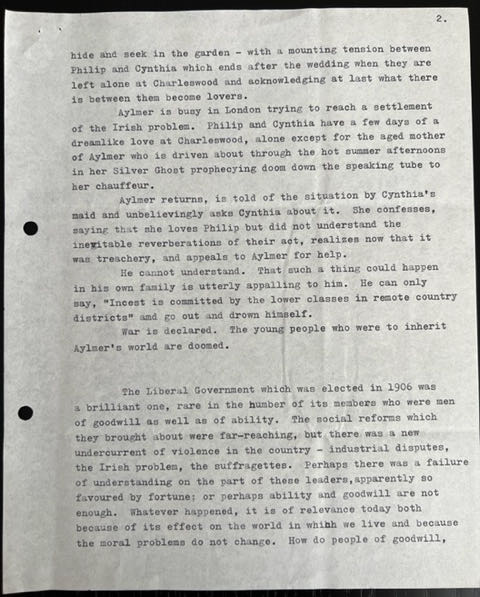

Statues in a Garden is set in the summer of 1914. Of the book, Colegate herself wrote, “This is a simple story about good and evil. Except that one is not quite sure which is which.” Upon first publication, The Guardian cites the “remarkable sense of the period” and summarizes the plot, “The family tragedy which it describes subtly echoes the larger social disintegration to come.”

For the film version, Blattner suggests, without naming anyone, “an English Director with a sensitive touch.” He is more explicit in suggesting potential cast: Elizabeth Taylor as Cynthia Weston, the wife. Colegate describes the character as “a famous beauty who takes her ideas and beliefs obediently from her husband but whose nature is far more passionate than his.”

Other Blattner choices were Michael Horden as Aylmer Weston, a cabinet minister; and Alan Bates or Terence Stamp as Philip Weston, the adopted son. Tiomkin had already suggested Edith Evans or Flora Robson as Aylmer Weston’s mother and had previously pursued Jeanne Moreau for a leading role.

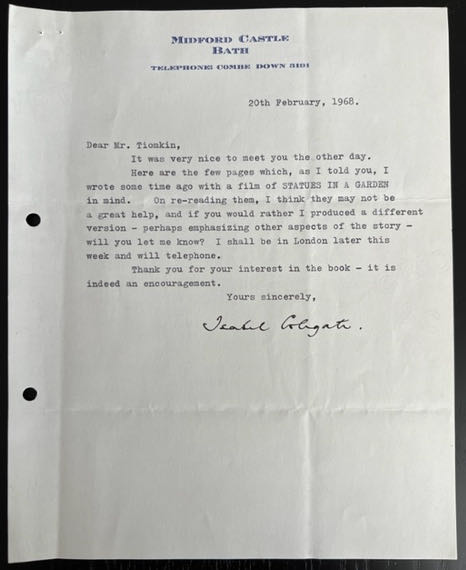

Tiomkin and Colegate meet in person in February 1968. Days later, Colegate writes to Tiomkin from her residence, Midford Castle near Bath—later owned for a stint by actor Nicolas Cage—thanking Tiomkin for his interest in the book, “it is indeed an encouragement.” Attached to the letter are a few pages written “some time ago with a film of STATUES IN A GARDEN in mind. On re-reading them, I think they may not be a great help.”

At the same time Tiomkin is communicating with Bercutt, he solicits feedback from Seven Arts Productions in London. (Warner Bros.-Seven Arts is in the early days of its corporate merger and Tiomkin would team with the company for his film, Tchaikovsky.) Upon reading Statues in a Garden, production manager and supervisor Raymond Anzarut does not have encouraging words concerning a film adaptation. “It is an extremely sweet story, very well written, but being so far removed from the contemporary scene it has little hope of captivating anybody’s enthusiasm in today’s world.” Anzarut sends a report to Warner Bros. in Hollywood and agrees to “periodically, revive interest in it in the hope we may strike lucky at the opportune moment.”

Tiomkin next approaches producer John Heyman, the founder and chairman of World Film Services in London, who writes, “I think in many ways it is a fascinating project” before passing the book on to his internal staff. Heyman has access to Elizabeth Taylor who is the lead actress in BOOM!, a film he was producing at the time.

With the eighteen-month option about to expire in January 1969, Tiomkin writes to Harold Matson to extend the option and encloses payment for the same.

When the six-month option expires, literary agent Anthony Jones offers a further option at terms that Tiomkin is not willing to accept. Jones works for A D Peters & Co.—a London firm associated with the New York office of Harold Matson Company—the literary agency that represents Colegate.

Jones, writing to Tiomkin’s attorney, Charles Levison, does not mince words. “I’m afraid that Mr. Tiomkin’s proposals are quite unacceptable and if he is not prepared to go above that then we might as well forget the whole thing.” The sticking point was that Tiomkin wanted past and future option payments to count toward the purchase price of the film rights and Jones’s proposal countered, “none of the earlier payments made by Mr. Tiomkin would be taken into account against this purchase price.” Jones ends the letter, “If he can’t agree to these terms I’m afraid we have no deal.”

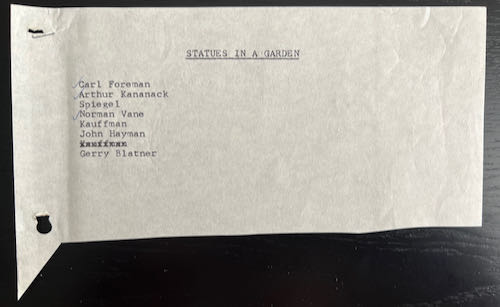

Levison writes to Tiomkin on August 18, 1969, outlining Jones’s final terms. That is the last item in the file, other than an undated slip of paper headed STATUES IN A GARDEN with a list of names, as below.

The Shooting Party remains the only Isabel Colegate novel to be adapted to the screen. Similar in theme and setting to Statues in a Garden—the story takes place in the Autumn of 1913—the 1984 film was scripted by Julian Bond, directed by Alan Bridges and starred James Mason, Edward Fox, and Dorothy Tutin. After the film was released several of Colegate’s earlier novels were re-issued.

Statues in a Garden was published as an e-book by Bloomsbury Publishing, London, in 2021. Goodreads.com cites the work as “A captivating portrait of a lost world, Statues in a Garden is a rediscovered masterpiece by one of the most important and neglected British female writers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.”

Sources

Correspondence courtesy of Olivia Tiomkin.

The Guardian, August 21, 1964. Plot line of Statues in a Garden.

Chicago Tribune Books Today, Books Published, March 13, 1966.

“Movie Call Sheet: Novel Rights for Tiomkin,” Los Angeles Times, November 4, 1967.

“Abe Greenberg’s Voice of Hollywood,” Valley Times, November 17, 1967. Contains blurb on Statues and casting Jeanne Moreau.

“Colegate, Isabel,” by Elizabeth Evershed, ProQuest Biographies, Ann Arbor: ProQuest, 2011.