by Warren M. Sherk

When one considers the music of Dimitri Tiomkin, jazz probably is not the first thing that springs to mind. The fact remains, however obscured by the passage of time, that jazz had a significant influence on the composer in his formative years, in Russia. In his pre-Hollywood career as a concert pianist, Tiomkin’s interest in modern music extended beyond classical to jazz, which he publicly defended as a uniquely American art form. He believed that Russian composers were predisposed to rhythmic effects in music and that the strong, exciting rhythms inherent in the folk music of his country of birth gave him a certain affinity for African American folk music.

On the heels of Black History Month, this article assesses the influence of this music on Tiomkin and looks at his association with some of the finest black musicians of the twentieth century, among them singers Nat “King” Cole, Mahalia Jackson, Eva Jessye, and Kitty White, and arrangers Benny Carter, Jester Hairston, Hall Johnson, and William Grant Still. Hairston, Tiomkin’s longtime choral arranger and conductor, once commented, “Tiomkin didn’t give a damn what color you were, so long as you could do the work.”

A new kind of sound

Dimitri Tiomkin, circa 1914

As a student at the St. Petersburg Conservatory, Tiomkin met Flora Davis, a young black nurse from New Orleans who was the mistress of Count Alexander Sheremetiev (1859–1931). Tiomkin had been introduced to the Russian nobleman and philanthropist by the composer Alexander Glazunov, the conservatory’s director, and was subsequently enlisted to teach piano to “Miss Ruby,” as Davis was known. She had brought with her sheet music for songs she had performed in cabaret and minstrel shows back in America. By using the sheet music as a teaching aid, Tiomkin was introduced to American popular music as influenced by black artists—a sound much different from the classical works he had been studying at the conservatory. At such an impressionable age, he was intrigued by the rhythm and syncopation he heard in the cakewalks, ragtime, and early jazz.

It was around this time that Tiomkin first heard Irving Berlin’s “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” at the Homeless Dog, a tune that Tiomkin says “swaggered, loud, rowdy, and insolent with its insistent pattern of dotted notes.” The music combined African American rhythms and styles in a way that soon would be commonplace for American composers from Berlin to George Gershwin. Tiomkin’s exposure to jazz did not end in Russia, however, as the music worlds of Paris and New York would later prove.

Poetry also had a lasting effect on Tiomkin, particularly the works of the Russian Romantic poet Alexander Pushkin (1799–1837), whose maternal grandmother was African. Olivia Tiomkin Douglas recalls the lifelong influence Pushkin had on Tiomkin: “Tchaikovsky wrote three operas based on Pushkin’s works, and for one of them, Eugene Onegin, Dimitri had to learn all the parts by heart in his early days at the conservatory in St. Petersburg. Tiomkin owned a set of watercolor paintings of the stage settings for Eugene Onegin, which he greatly cherished, he had books of poems by Pushkin, and Pushkin was very much part of his cultural background. He knew by heart many of Pushkin’s works, and he was always interested in his black roots. I think that Dimitri admired his versatility—apart from Pushkin’s serious dramatic works he also wrote (according to Dimitri) a collection of erotic poems—and it interested him that although Pushkin’s works were so essentially Russian, he also had African blood in him. Dimitri used the Tchaikovsky-Pushkin collaboration many times in Tchaikovsky.”

When Tiomkin arrived in Paris with pianist Michael Khariton in the mid-1920s, he experienced American music in the form of jazz and the blues. Wandering through the cabarets of the City of Light, he heard American jazz bands and tried to “catch the tricky rhythm” on the piano. Wishing to master the skill himself, he took lessons from a jazz pianist in New York. As a result, the rhythms and harmonies of jazz soon found their way into the budding composer’s music. In Hollywood, Tiomkin would often hire black musicians for his film work.

Collaborating with African American choral directors

Hall Johnson

One of the first black musicians with whom Tiomkin worked in Hollywood was Hall Johnson (1888–1970). The choral director, composer, and arranger was “one of the two American composers who elevated the African American spiritual to an art form, comparable in its musical sophistication to the compositions of European Classical composers.” After founding the Hall Johnson Choir in New York in the mid-1920s, Johnson devoted his life’s work to “preserving and interpreting the rich legacy of African American music that developed under slavery.”

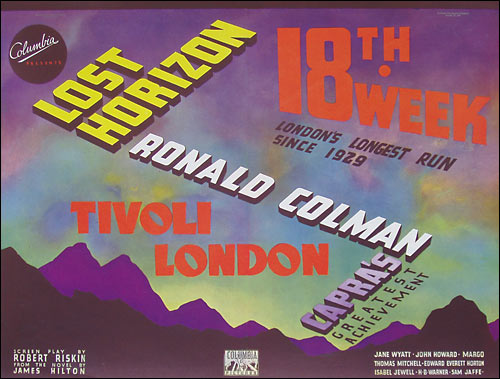

Lost Horizon half sheet, US, style B

When his choir was called west to California in 1935 for the film version of The Green Pastures, Johnson established a presence in Hollywood that lasted about a decade. (He returned to New York after World War II.) Tiomkin heard the Hall Johnson Choir in a concert and, as Jester Hairston recalls, “went crazy for the sound.” The group was signed by Columbia Pictures in November 1936 to sing on Tiomkin’s background score for the adventure-fantasy film Lost Horizon, directed by Frank Capra. Although the Los Angeles Times reported that the choir would be singing in the Tibetan language, Tiomkin said later that the words were made up for the film. The Tibetan chants can be heard to good effect in the film’s “Entrance to Shangri-La” scene. When Tiomkin conducted a suite from Lost Horizon at the Hollywood Bowl in August 1938, the Hall Johnson Choir performed live, backed by the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

After Lost Horizon, Capra introduced Tiomkin to an American music anthology with music by Stephen Foster, along with Negro spirituals, Mississippi River songs, and songs from the cotton fields. This probably influenced the choice of music for Capra’s Meet John Doe, which is interspersed with several Foster tunes, including “Hard Times Come Again No More” and “Some Folks Do.” Friction arose between composer and director when Capra cut the Negro spiritual that figured prominently in the emotional impact of the score. For the film’s climax, Tiomkin wove together a resonating requiem based on “Deep River” with the hopeful strains of “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, both performed by the Hall Johnson Choir. When Capra chose an alternative, brighter ending, Tiomkin’s symphonic lament was cut in the process in favor of Beethoven, followed by a medley of Americana that included “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” and “Oh Susanna.” After a brief chill, Capra recruited Tiomkin to score his army orientation and information films, including the “Why We Fight” series. When Tiomkin sought out a choral arranger for The Negro Soldier in 1944, he looked up Johnson’s assistant, Jester Hairston, resulting in a lengthy and fruitful collaboration.

Jester Hairston

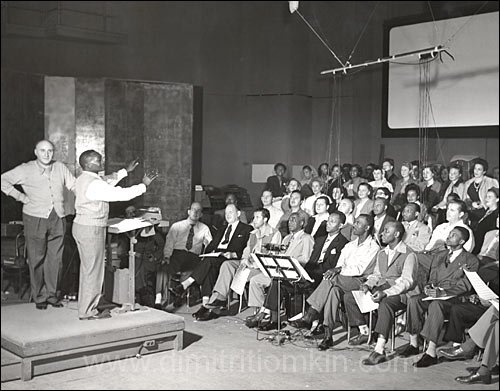

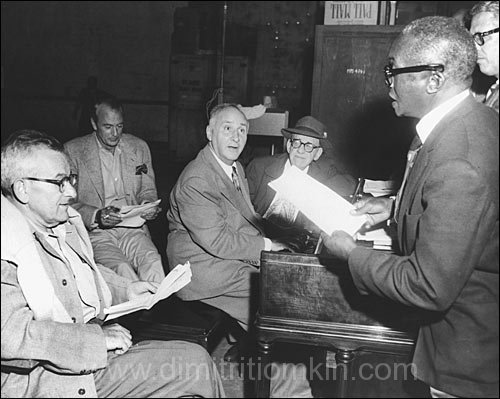

Jester Hairston with Dimitri Tiomkin, circa 1950s

Born in North Carolina at the turn of the century, Jester Hairston (1901–2000) found his calling when he joined the Hall Johnson Choir in New York in the early 1930s. He quickly rose to the position of assistant conductor, where his duties included rehearsing and preparing the ensemble for performances. When Hairston accompanied the choir to California for film work, he saw that Johnson preferred conducting live concert performances to suffering through the tedium and repetition of film studio recording sessions. At some point during the drawn-out sessions for Lost Horizon, Hairston took over conducting duties when Johnson fell ill. Hairston’s positive attitude and willingness to adapt gave him a leg up on his mentor, who balked at requests to break down a performance into small pieces for recording purposes. As Hairston once said, “If you want three bars, I’ll do three bars.” Tiomkin was pleased with Hairston’s work and told him that he would use him again in the future. (At this point Tiomkin’s film composing career was still in its infancy.) It took a few years before the Tiomkin-Hairston collaboration got off the ground, but when it did, with Negro Soldier, their unique professional and personal relationship lasted a decade.

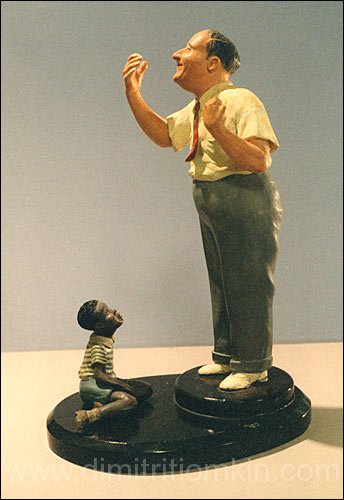

Dimitri Tiomkin statuette commemorating Negro Soldier

During the war effort, the U.S. government sought to document the participation of “Negro Americans” serving their country in previous wars in which the United States was involved. Originally intended to be screened solely for black troops—ironic, considering the film pointedly tried to avoid such issues as segregation—Negro Soldier was released commercially after various groups, inspired by its message, lobbied for exposing it to a wider audience. As music director, Tiomkin selected and hired composers and arrangers, who were paid by the government through Paramount Pictures. They included several blacks, including Calvin Jackson, William Grant Still, and Phil Moore. Arranger Still and choir master Hairston, both of whom had worked on Lost Horizon, received $75 a week and a flat fee of $275, respectively, for Negro Soldier. For the twelve-voice choir, Hairston arranged the spirituals that supplemented Tiomkin’s score, including a rousing rendition of “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho,” which marks the film’s conclusion. Both Tiomkin and Hairston attended the Los Angeles premiere of the film at the Ambassador Hotel Theater in April 1944.

After the war, Tiomkin called on Hairston for such films as Angel on My Shoulder (1946), Duel in the Sun (1947), It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Red River (1948), Home of the Brave (1949), and My Six Convicts (1952). In the late 1940s, Hairston looked back on the situation in Hollywood. “Before the war the studios only called us when they had ‘Negro music’ to be sung,” he said. “We were starving between pictures. So I organized my own choir, hired the best voices I could find, irrespective of color—and notified the studios we were capable of doing all music from Bach to Basie.”

A cursory glance at Hall Johnson’s film credits confirms Hairston’s statement. The Tiomkin-scored films, such as Lost Horizon and Meet John Doe, stand out from the black-themed films and musicals, such as Way Down South and Cabin in the Sky. When a film studio questioned Tiomkin’s request to hire a black choir to sing classical music, he reportedly replied, “It’s my music, and I like the sound.” An added benefit was that sound’s compatibility with the recording and playback equipment available in the 1930s. While certainly state-of-the-art, the equipment had some well-known shortcomings when it came to recording music. Tiomkin must have realized that the low, warm tones of African American singers reproduced well in theatrical settings. Like Tiomkin, Hairston preferred the soft, round, mellow quality of Negro singers, particularly when blended with the more piercing tone quality of white singers.

Tiomkin signed the Jester Hairston Choir to perform the choral passages in the 1949 United Artists thriller Red Light. The choir Hairston assembled consisted of approximately twenty-five white and fifteen black singers to perform in the church scenes that incorporated classical music, such as Franz Schubert’s “Ave Maria.” That same year seventeen Negro and white singers are heard as the convent choir in Portrait of Jennie. To capture the emotions of the Egyptian Pyramid builders in the 1955 film Land of the Pharaohs, Tiomkin did not want a polished sound from the choir. So, he asked Hairston to assemble an eighty-voice mixed choir that could handle the symphonic aspects of the music and serve as the voice of the Egyptians.

Regarding the vocal score, Frank Lewin wrote in Film Music Notes that “an impressive use of the chorus is made to portray the spirit of willingness with which the Egyptians answer the call to work…. The people march to work shouting in song their devotion…in the quarries where great blocks of stone are chipped out of the rock the music blends with the sound effects of the chisels.” Anna Wheeler Gentry points out some of the varied requirements of the vocal score: “Other scenes required Hairston to conduct various choral sequences including the sound of girls’ voices in the distance, and ‘funeral songs of joy’ where the choral ensemble becomes an integral part of the musical conceptualization—illustrating the moment of rebirth—through vocal color.”

Tiomkin’s devotion to Hairston was evident. “There are many choirs and choirmasters in Hollywood and they all compete like crazy,” the composer said. “But Jester’s work for me and for people like John Ford, Frank Capra, and Anatole Litvak has been so impressive that I, at least, prefer only to work with Hairston. I know that he can get music from his singers.”

Dimitri Tiomkin rehearsal with Jester Hairston (far right)

By the mid-1950s, Hairston’s choir was well established as an interracial group of professional singers for which Hairston contributed his arrangements of gospel and folk music for concert performances. Hairston’s association with Tiomkin led to other film offers. “When they found out I could please the greatest composer in town, they began to call me for other pictures,” he remarked. A notable result is Hairston’s spiritual, “Amen,” for Lilies of the Field. Tiomkin expressed admiration for Hairston’s work on Carmen Jones, a black version of Bizet’s opera Carmen. After their professional relationship ended in the mid-1950s with Friendly Persuasion, the two stayed in touch. Hairston, who considered Tiomkin his friend and teacher, sent his 1970s disc recordings, including “Jester Hairston and His Chorus: A Profile of Negro Life in Song,” on which he inscribed, “My sincere appreciation to you for all the many films we did together.” Hairston lived nearly one hundred years. His New York Times obituary summed up his life as one dedicated “to preserving the authenticity of the rural black voice.”

The New York jazz scene

Jazz infused Tiomkin’s musical world in New York, from Harlem jazz clubs to vaudeville tours, where his two-piano act often shared the same program with Negro bands. While fascinated by the offbeat rhythms and frenzied free-for-all improvisations, Tiomkin’s strict musical training made it difficult for him to master jazz idioms. To supplement his classical training, he took lessons from a New York jazz pianist, whom he refers to only by his surname, “Henderson.” Henderson caused a stir when he called on Tiomkin’s apartment and the doorman notified Tiomkin that the black pianist would have to take the service elevator. Not fully understanding American racial distinctions, Tiomkin was floored. Tiomkin describes the pianist as “six and a half feet tall, black, and dressed to perfection,” with an expensive necktie. (While it’s possible that “Henderson” is the bandleader-pianist Fletcher Henderson or his brother, Horace, further research is needed. Fletcher was indeed tall; he appears to be around six feet in archival photographs. In a French-language program, the New York critic Leonard Liebling writes that in the opinion of W. G. Henderson, no one is superior to Tiomkin in the field of blue jazz.)

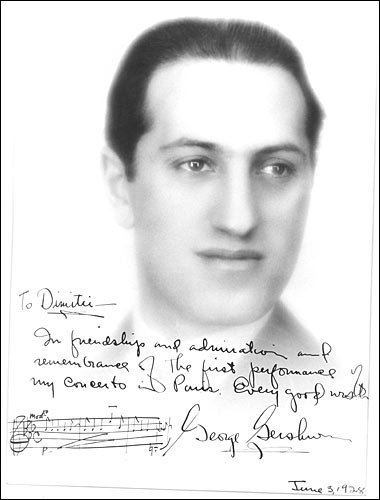

Photo inscribed by George Gershwin

Immersed in jazz, Tiomkin would listen repeatedly to George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue as played by the composer on a Duo-Art player piano roll. Tiomkin hails its originality and seemingly inspired improvisation as a masterpiece of American popular music. When Albertina Rasch set the music to a ballet, Tiomkin played one of the two piano parts. At Tiomkin’s urging, the noted Hollywood caricaturist and artist John Decker painted a six-by-eight-foot impressionistic canvas depicting the evolution of jazz. Tiomkin hung the painting behind his piano for inspiration prior to his European tour, which included the premiere performance of Gershwin’s Concerto in F, in Paris.

In 1930 Tiomkin joined in a public debate with composer William Wakefield Cadman over the future direction of musical influence for motion pictures. Cadman argued for classical music and declared “the motion picture industry will gain neither dignity nor respect from the encouragement of jazz, which is a shallow and soulless mode of musical expression.” Tiomkin countered that jazz reflected the spiritual and mental life of the people.

Gone “jazzique”: Tiomkin and African American arrangers

Russell Wooding

Prior to the Cadman debate, Tiomkin began work on a project while still in New York that included arranger Russell Wooding. In his youth, Duke Ellington played in a Wooding ensemble, and as a bandleader Wooding became a fixture on Broadway in the early 1930s. A July 1929 article in Variety, “Tomkin [sic] Preparing for Concert Work With Colored Pianists,” tells of Tiomkin’s rehearsals with two colored pianists backed by Le Roy Smith’s colored orchestra from Hot Chocolates. That wildly successful all-black musical revue had just opened on Broadway and introduced Fats Waller’s now classic “Ain’t Misbehavin'” in performances by the Russell Wooding Jubilee Singers and trumpeter Louis Armstrong in his Broadway debut. The Variety article went on to say that Wooding was to arrange some new jazz-type numbers from original compositions by Tiomkin, who had gone “jazzique.” The work may be related to “Creole Blues” or may have been a new piece cut short when Tiomkin and Albertina Rasch left New York for Hollywood soon thereafter.

Calvin Jackson

Tiomkin’s hiring of twenty-five-year-old Calvin Jackson (1919–1985) for Negro Soldier was a stepping stone for that young arranger-pianist who went on to orchestrate at MGM. Jackson composed and arranged a fair bit, about one-fifth, of Negro‘s score. Jackson later recorded with his fellow Negro Soldier arranger, Phil Moore (1918–1987), before forming his own group, the Calvin Jackson Quartet. Jackson’s 1961 album, “Jazz Variations on Movie Themes,” features music by Tiomkin from The Alamo, The High and the Mighty, and High Noon. He previously cut a Reprise seven-inch promo (R-20009) of the High Noon theme.

William Grant Still

Under contract to Columbia Studios as a composer and orchestrator in the 1930s, William Grant Still (1895–1978) orchestrated Tiomkin’s “Pigeon Music” cue for Lost Horizon (1937) and shared the orchestration with George Parrish for the “Procession” cue. Still knew Hall Johnson from their days together in the “Shuffle Along” orchestra in New York in the mid-1920s. This film may have introduced Tiomkin to Still, the “Dean of American Negro Composers,” best known for his much-performed first symphony, “The Afro-American.” The head of Columbia’s music department, Howard Jackson, whom Tiomkin knew in New York, brought Still in. Still worked for Tiomkin on three 1944 films: Ladies Courageous; Negro Solder, for which he orchestrated about one-fifth of the score; and Tunisian Victory.

Benny Carter

Benny Carter (1907–2003) was among the first black arrangers and musicians accepted by the Hollywood studio system in the 1940s. In the 1960s he supplied arrangements for The Guns of Navarone and the love theme from 36 Hours, “A Heart Must Learn to Cry,” popularized by vocalist Irma Curry on Vee Jay Records. Around this time Carter inspired and mentored the young Quincy Jones (b. 1933). Jones later scored the 1969 Western MacKenna’s Gold, co-produced by Tiomkin.

Black musicians, civil rights, and the union in Los Angeles

Although the American Federation of Musicians’ Locals in Los Angeles were segregated, this didn’t keep whites and blacks from working together. Los Angeles Local 767, known as the Colored Musicians Union, was formed in 1920. In 1953 the Colored union merged with the white Local 47. According to Florence Brantley, recording secretary for Local 767, Tiomkin used the “colored” Local for his films. In addition to black arrangers, Tiomkin often hired black singers, pianists, and other musicians.

Florence Cadrez “Tiny” Brantley is a perfect example. A Los Angeles native, she met Hall Johnson and Jester Hairston when she served as rehearsal pianist during the filming of Green Pastures. She took on that role for Johnson’s choir, for both concert and film work, and sought out additional singers from the local talent pool. Johnson and Hairston introduced her to Tiomkin during Lost Horizon. Later she served as rehearsal pianist on Negro Soldier, Duel in the Sun, and Portrait of Jennie, and she frequentlyaccompanied Jester Hairston’s choir in concerts.

As chairperson of the committee for amalgamation, Benny Carter was instrumental in the fight for equality. Arranger and union activist Marl Young later related how film and television music played an important role in desegregating the union. Interestingly, the bulk of Tiomkin’s hiring of African Americans took place prior to the merge. In recognition, Tiomkin was made an honorary member of the Colored Musicians Union.

Carter, Nat Cole, Frankie Laine, and others Tiomkin worked with were involved in the historic fight for civil rights. Carter and Cole had to overcome restrictive covenants in order to live in predominantly white neighborhoods in Los Angeles. And Tiomkin worked with Cole prior to the singer’s 1956-57 television show that was canceled after it failed to attract a national sponsor due to the perception that it catered only to a black audience. Singer Frankie Laine (1913–2007), who popularized Tiomkin’s song from High Noon in 1952, was the first white artist to appear as a guest on Cole’s show. Laine himself was “the most successful of the black-influenced white singers who came to prominence in the post-war era,” according to his obituary in the London Daily Telegraph.

A time to sing

Nat “King” Cole

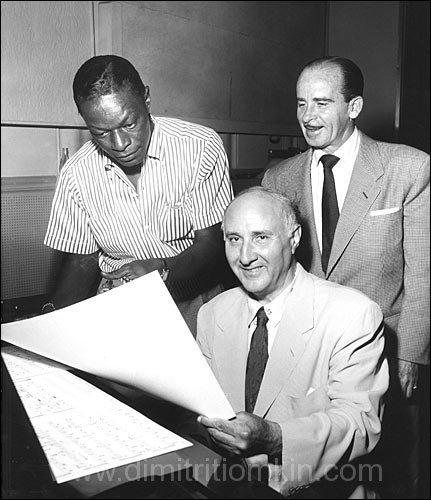

Dimitri Tiomkin with Nat King Cole and Ned Washington

Although Nat “King” Cole (1919 –1965) did not work directly with Tiomkin until the 1950s, two films scored by Tiomkin contained a musical connection to the recording artist. In 1946 Cole sang “The Christmas Song” for It’s a Wonderful Life, and in 1949 the song “Portrait of Jennie,” by J. Russell Robinson and Gordon Burdge, became a hit even though it was not heard in the film of the same name.

In 1953 Cole covered Tiomkin’s title song from Return to Paradise in a memorable Nelson Riddle arrangement. Incidentally, another black artist, bebop bassist Douglas Watkins (1934-1962), recorded a thirteen-minute version of “Return to Paradise” for “Watkins at Large,” featuring guitarist Kenny Burrell and others, which was issued by jazz label Transition Records in 1956.

As a Capitol artist, Cole recorded the title songfor The Adventures of Hajji Baba inJuly 1954. “Hajji Baba,” or the “Persian Lament,” was written by Tiomkin and Ned Washington and is heard over the opening credits in an arrangement by Nelson Riddle and intermittently throughout the film in Tiomkin’s underscore. Although the movie failed to connect with audiences, the seven-inch single (Capitol 2949) topped the pop charts that year at No. 14. The following year it became track six on Cole’s “Unforgettable” album. For another take on “Hajji Baba,” listen to Johnny Campbell’s rhythmic jazz version from a 1999 album, available on iTunes.

Kitty White

Jester Hairston introduced singer and pianist Kitty Jean Bilbrew White (1923–2009) to Tiomkin. When Hairston heard the voice of the twenty-seven-year-old singer, he immediately began using her for film gigs. White’s excellent sight-reading skills proved advantageous for studio recording sessions. (Hairston recalls that many of the Negro Soldier singers did not read music, and some Tiomkin scores dispensed with key signatures, making sight reading more difficult.)

White hailed from a musical family well known around Central Avenue, then the center of black Los Angeles and the jazz scene, and Tiny Brantley was a friend of White’s daughter. White’s mother, A. C. Harris Bilbrew (1888–1992), was a vaudeville performer who also worked in radio and film. (A Los Angeles County Library branch is named in her honor.) A. C. Bilbrew’s father founded the First Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in Los Angeles, where A.C. served as choir director. White’s uncle, Omri Watson Bilbrew (1890–1988), was one of eight African American charter members of the “colored” union. Kitty White’s daughter recalls Tiomkin’s visits to their home to conduct sessions, and in turn, White would accompany Hairston to Tiomkin’s home in Windsor Park, where her piano stylings provided source material for some of Tiomkin’s scores.

In 1955 White was signed by Mercury Records, and her first LP was subtitled “A New Voice in Jazz.” By that time she already had sung the background vocal on “Return to Paradise.” Tiomkin loved her voice, and turned to her whenever he needed a female vocalist for the demonstration records that were commonly made to audition film songs for producers, directors, and studio heads. As an independent composer, Tiomkin was usually responsible for arranging and supervising these recordings, which often took place at a local studio. Some demos were used as recorded, some were re-recorded with a more commercial singer, and some ended up on the shelf. In the case of White’s vocal for “The Last Train,” written by Tiomkin and Paul Francis Webster for the 1959 film Last Train from Gun Hill, the idea was to repeat the theme several times throughout the film, but instead of repeating the main title lyric each time, Webster wrote several sets of lyrics, each of which commented on the development of the story. Eventually the idea was scrapped, and the song was placed on the shelf.

For 1958’s The Old Man and the Sea, White cut a demo of Tiomkin’s song “I Am Your Dream” at Gold Star Recording Studios in Hollywood, soon to be the home of Phil Spector’s groundbreaking Wall of Sound. The “song” is heard only as a background instrumental in the film. GNP Records later released the White recording as a seven-inch single (GNP 141X).

Mahalia Jackson

Gospel singer Mahalia Jackson (1911–1972) was at the height of her career when Tiomkin hosted a party for her in 1961, a few days before she performed in concert at the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles. Hollywood gossip columnist Hedda Hopper reported that Jackson, who almost exclusively performed religious songs, rejected the first song Tiomkin sent her for its lack of Scripture. “Then he sent another of his songs that had some words from Proverbs,” Jackson said. “I love it and am happy to say it’s successful.” She is probably referring to “The Green Leaves of Summer,” written by Tiomkin for The Alamo. In it, Paul Francis Webster writes the following lyric:

A time to be reapin’, a time to be sowin’,

The Green Leaves of Summer are callin’ me home.

This is thematically similar to the biblical passage in Ecclesiastes 3:1:

To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under heaven.

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, and a time to reap that which is planted.

Tiomkin with Mahalia Jackson and John Green, 1963

Jackson performed the song at a legendary concert at the Hollywood Bowl in September 1963. The Composers and Lyricists Guild of America presented the live concert featuring music by Tiomkin, Elmer Bernstein, Jerry Goldsmith, Bernard Herrmann, Henry Mancini, Jerome Moross, Alfred Newman, Alex North, Miklos Rozsa, Max Steiner, Franz Waxman, and John Williams. Some of the music appeared on a Columbia LP at the time, and in 1995 Sony issued a CD with previously unreleased tracks. In addition to Stanley Wilson’s arrangement of “Green Leaves,” a suite of music from High Noon—specially arranged for the concert by Morton Gould—was performed.

The crowd of 10,000 must have been enthralled that night by Jackson’s hauntingly beautiful rendition. On the recording, her performance—made indelible by her deep contralto voice and her unique and drawn-out pronunciation of the word time (“tie-eeem”)—is followed by passionate “Bravos” and waves of enthusiastic applause. Tiomkin seemed attracted to voices with unique characteristics, and Jackson’s voice, though untrained in the classical sense, had been nurtured and cultivated in a childhood spent singing in her father’s Baptist church in New Orleans and listening to phonograph recordings of the blues. The combination of Jackson’s soulful vocal embellishments and Wilson’s understated orchestral accompaniment, with Tiomkin conducting, turns this performance of “Green Leaves” into one for the ages. The divine Sarah Vaughan (1924–1990) covered “Green Leaves of Summer” for Roulette Records (R-4343) in a Billy May arrangement from 1960.

Cakewalks and Creole blues: The effect of African American music on Tiomkin’s work

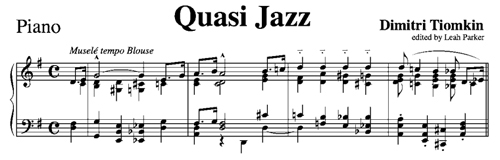

One of Tiomkin’s early piano compositions, “Quasi-Jazz,” features a ragtime bass pattern and elements of the cakewalk. The work created a stir in musical circles when Tiomkin introduced it on his concert of modern classical piano music at Town Hall in March 1927. The New York Times called it “a new expression of syncopation” and its reception heralded an encore. Shortly after the concert, the composer announced he would begin work on an American jazz ballet for a forthcoming Albertina Rasch Broadway revue—probably “Creole Blues,” completed in November 1927, which two years later became the second movement of his Mexican Suite.

Tiomkin performed “Quasi-Jazz” at Carnegie Hall in late 1927. He had been originally scheduled to open Fortunate Gallo’s new theater, but when the opening was delayed, he played Carnegie Hall instead. An annotation in an unused Gallo Theater program suggests that “Quasi-Jazz” and “Impression of the Blues,” which Tiomkin later played in a recital at Maison Gaveau in Paris, are the same piece. Music critic Sigmund Spaeth wrote that “Impression of the Blues” represented “the reaction of a Slavic temperament to the negroid syncopations of the day.”

Tiomkin performed “Quasi-Jazz” at Carnegie Hall in late 1927. He had been originally scheduled to open Fortunate Gallo’s new theater, but when the opening was delayed, he played Carnegie Hall instead. An annotation in an unused Gallo Theater program suggests that “Quasi-Jazz” and “Impression of the Blues,” which Tiomkin later played in a recital at Maison Gaveau in Paris, are the same piece. Music critic Sigmund Spaeth wrote that “Impression of the Blues” represented “the reaction of a Slavic temperament to the negroid syncopations of the day.”

For a 1930 concert at the Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles, Tiomkin played “Quasi-Jazz” and premiered a modernist piano piece by Bernard Rogers (1893–1968) titled “Little Africa,” which the composer dedicated to Tiomkin. (Bernard Rogers went on to become a well-regarded piano teacher at the Eastman School of Music and served on the editorial board of Musical America.) It was apparently a little too modernist: “Its lurching negroisms may be interesting to a Russian program maker, but not to American ears,” commented one reviewer, Bruno David Ussher, who also wrote about Tiomkin’s film music for the Los Angeles Daily News in the late 1930s. Unlike “Quasi-Jazz,” which combined jazz elements in a classical setting, Tiomkin’s “Scarlet Jazz” from 1929 wholeheartedly embraces the idiom through its harmonies, voicings, and rhythm. The Suite Choreographique, or Choreographic Suite, was premiered at the Hollywood Bowl with a syncopated last movement, “Exotica,” inspired by American blues. “Modernistic Impressions of the Blues,” ballet music from 1931, continued Tiomkin’s African American-influenced compositions.

The Albertina Rasch Dancers presented a 1932 concert at Lewisohn Stadium in New York that featured three ballet numbers influenced by African American music. “Cakewalk,” composed prior to Tiomkin’s arrival in America according to the program notes, may be one of his earliest original compositions. By this time the cakewalk had crossed over from its Negro dance origins and found acceptance with white audiences. Likely conceived for solo piano, the marchlike work was orchestrated by Ferde Grofé in New York before he moved to Santa Monica, California, where he wrote his memorable Grand Canyon Suite.

Grofé orchestrated another Tiomkin work on the program, “Negro Chant.” Hugo Riesenfeld conducted the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra and a choir supplemented by the forty-voice Eva Jessye Choir. Jessye (1895-1992), a leading African American choral director, had assembled her group from members of the Dixie Jubilee Singers and led them in spirituals, ragtime, and jazz in a variety of mediums, including film and radio. Incidentally, prior to meeting Hall Johnson, Jester Hairston had been introduced to spirituals as a member of Jessye’s choir. The work, titled simply “Chant,” was performed at the Hollywood Bowl in 1933. Music in the Dimitri Tiomkin Collection at USC indicates at one time the work bore the title “Africano” and the subtitle “Native Jungle Ceremonial Dance.”

Two other Tiomkin pieces on the program incorporated jazz elements. The “Scherzo Humoresque” was full of jazzy accents and blue notes. The work was later performed at the Hollywood Bowl under the title “Ambition.” The closing ballet, “To-Day,” was conceived as “the apotheosis of modern eccentric jazz, atonal, strongly syncopated, with cross rhythms.” “To-Day” became Tiomkin’s “Mars Ballet.”

Tiomkin’s musicological-like assessment of white America’s acceptance and interest in early jazz is apparent in interviews in the 1920s with Sigmund Spaeth and others. “Jazz is not so much a revolt against conventional music in general as it is a revolt against conventional popular music,” the composer would argue. “If you listen to the songs of the gay nineties, with their absurd sentimentalities, or the watery two-steps and polkas of an earlier day, you will realize that popular music in America was sadly in need of pep. It acquired this ingredient through the development of rag-time and jazz.”

Jazz rhythms and harmonies became an integral part of Tiomkin’s music vocabulary, and he recognized their creative significance before much of white America did. At a time when it was not the norm, he hired black musicians and vocalists for dramatic films aimed at white audiences. He did not shy away from visiting homes in predominantly black neighborhoods and hiring black musicians for music traditionally performed by whites. A producer once questioned the ability of black singers to perform classical or film music. Tiomkin reportedly had this simple reply: “I don’t see color, I hear music.”

© 2007 Volta Music

Sources

- “Hairston and Tiomkin: Composers and Choral Collaborators” by Anna Wheeler Gentry (accessed at www.geocities.com/karamaev/hairston.html)

- The Dimitri Tiomkin Collection at the University of Southern California (thanks to Ned Comstock)

- The Los Angeles Times and New York Times, accessed through ProQuest

- Central Avenue: Its Rise and Fall, 1890-c.1955: Including the Musical Renaissance of Black Los Angeles by Bette Yarbrough Cox (BEEM Publications, 1996)

- “Spirituals, Reels, Hoe Downs and Blues” by Hall Johnson in Music and Dance in California (Bureau of Musical Research, 1940)

- Unpublished 1994 audio interview with Jester Hairston, interviewed by Phil Lehman

- “Land of the Pharaohs” by Frank Lewin, Film Music (May-June 1955), page 19

- “The Negro’s Rise” by Clarence Muse in Music and Dance in California (Bureau of Musical Research, 1940)

- “Lost Horizon: An Account of the Composition of the Score” by William H. Rosar, Film Music Notebook (1978), pages 40-52

- “Dimitri Tiomkin and the Army Orientation and Information Films (1942-1945)” by Warren Sherk, The Cue Sheet (October 2005), pages 4-21

- www.goldstarrecordingstudios.com

- www.wikipedia.com